opengl draw 2d text 3d scene

Text Rendering

In-Practice/Text-Rendering

At some stage of your graphics adventures yous will want to draw text in OpenGL. Reverse to what y'all may expect, getting a elementary string to render on screen is all just easy with a low-level API like OpenGL. If you don't care most rendering more than 128 different same-sized characters, so information technology's probably not too hard. Things are getting hard as soon as each character has a different width, top, and margin. Based on where yous live, you may as well demand more than 128 characters, and what if you want to express special symbols for like mathematical expressions or sheet music symbols, and what almost rendering text from elevation to bottom? Once you think nearly all these complicated matters of text, information technology wouldn't surprise you that this probably doesn't belong in a low-level API similar OpenGL.

Since there is no support for text capabilities within OpenGL, it is up to u.s.a. to define a arrangement for rendering text to the screen. There are no graphical primitives for text characters, we have to get artistic. Some example techniques are: drawing alphabetic character shapes via GL_LINES, create 3D meshes of letters, or return graphic symbol textures to 2D quads in a 3D surroundings.

Virtually developers choose to return character textures onto quads. Rendering textured quads by itself shouldn't exist besides hard, only getting the relevant character(s) onto a texture could evidence challenging. In this affiliate we'll explore several methods and implement a more advanced, but flexible technique for rendering text using the FreeType library.

Classical text rendering: bitmap fonts

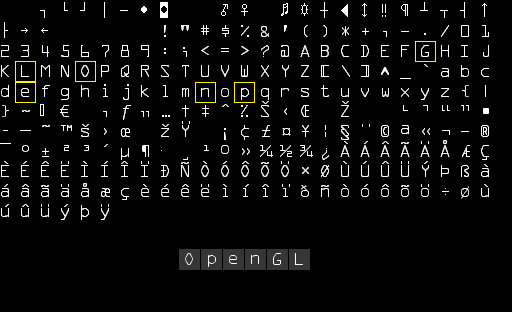

In the early days, rendering text involved selecting a font (or create one yourself) you'd similar for your application and extracting all relevant characters out of this font to place them within a single large texture. Such a texture, that nosotros telephone call a

Hither you tin can run into how we would render the text 'OpenGL' past taking a bitmap font and sampling the corresponding glyphs from the texture (carefully choosing the texture coordinates) that we render on peak of several quads. By enabling blending and keeping the background transparent, we will end upward with just a cord of characters rendered to the screen. This item bitmap font was generated using Codehead's Bitmap Font Generator.

This arroyo has several advantages and disadvantages. It is relatively easy to implement and because bitmap fonts are pre-rasterized, they're quite efficient. However, it is not peculiarly flexible. When you want to use a different font, you need to recompile a complete new bitmap font and the system is limited to a unmarried resolution; zooming will chop-chop prove pixelated edges. Furthermore, it is limited to a small character gear up, so Extended or Unicode characters are often out of the question.

This approach was quite pop dorsum in the day (and still is) since it is fast and works on any platform, merely every bit of today more flexible approaches exist. One of these approaches is loading TrueType fonts using the FreeType library.

Modern text rendering: FreeType

FreeType is a software development library that is able to load fonts, render them to bitmaps, and provide support for several font-related operations. It is a pop library used by Mac OS 10, Coffee, PlayStation, Linux, and Android to name a few. What makes FreeType particularly attractive is that it is able to load TrueType fonts.

A TrueType font is a collection of character glyphs not divers by pixels or any other not-scalable solution, only by mathematical equations (combinations of splines). Similar to vector images, the rasterized font images tin be procedurally generated based on the preferred font peak you'd like to obtain them in. By using TrueType fonts you can easily render graphic symbol glyphs of diverse sizes without any loss of quality.

FreeType can be downloaded from their website. You lot tin cull to compile the library yourself or employ one of their precompiled libraries if your target platform is listed. Be sure to link to freetype.lib and make sure your compiler knows where to detect the header files.

So include the appropriate headers:

#include <ft2build.h> #include FT_FREETYPE_H #include <FreeType/ft2build.h> volition likely cause several header conflicts. FreeType loads these TrueType fonts and, for each glyph, generates a bitmap image and calculates several metrics. Nosotros can extract these bitmap images for generating textures and position each grapheme glyph accordingly using the loaded metrics.

To load a font, all we take to exercise is initialize the FreeType library and load the font as a arial.ttf TrueType font file that was copied from the Windows/Fonts directory:

FT_Library ft; if (FT_Init_FreeType(&ft)) { std::cout << "ERROR::FREETYPE: Could not init FreeType Library" << std::endl; return -one; } FT_Face confront; if (FT_New_Face(ft, "fonts/arial.ttf", 0, &face)) { std::cout << "Mistake::FREETYPE: Failed to load font" << std::endl; return -1; } Each of these FreeType functions returns a non-goose egg integer whenever an mistake occurred.

Once we've loaded the face, we should define the pixel font size nosotros'd like to extract from this face up:

FT_Set_Pixel_Sizes(face, 0, 48); The role sets the font's width and height parameters. Setting the width to 0 lets the face dynamically calculate the width based on the given height.

A FreeType face hosts a collection of glyphs. We can set 1 of those glyphs equally the active glyph past calling

if (FT_Load_Char(face, 'Ten', FT_LOAD_RENDER)) { std::cout << "ERROR::FREETYTPE: Failed to load Glyph" << std::endl; return -1; } By setting FT_LOAD_RENDER equally i of the loading flags, nosotros tell FreeType to create an 8-fleck grayscale bitmap image for united states of america that we can access via face->glyph->bitmap.

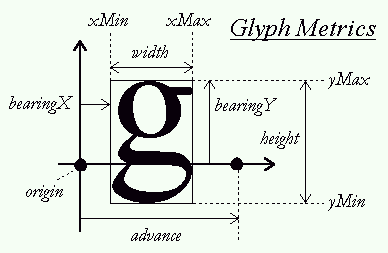

Each of the glyphs we load with FreeType however, practise not have the same size (as nosotros had with bitmap fonts). The bitmap image generated by FreeType is merely big enough to contain the visible part of a grapheme. For example, the bitmap image of the dot character '.' is much smaller in dimensions than the bitmap image of the character 'X'. For this reason, FreeType likewise loads several metrics that specify how large each character should be and how to properly position them. Next is an image from FreeType that shows all of the metrics it calculates for each grapheme glyph:

Each of the glyphs reside on a horizontal

- width: the width (in pixels) of the bitmap accessed via

face->glyph->bitmap.width. - height: the height (in pixels) of the bitmap accessed via

face->glyph->bitmap.rows. - bearingX: the horizontal bearing due east.g. the horizontal position (in pixels) of the bitmap relative to the origin accessed via

face up->glyph->bitmap_left. - bearingY: the vertical begetting e.g. the vertical position (in pixels) of the bitmap relative to the baseline accessed via

face->glyph->bitmap_top. - accelerate: the horizontal accelerate due east.g. the horizontal altitude (in i/64th pixels) from the origin to the origin of the adjacent glyph. Accessed via

face->glyph->advance.x.

We could load a character glyph, retrieve its metrics, and generate a texture each time we desire to render a graphic symbol to the screen, simply it would exist inefficient to do this each frame. We'd rather shop the generated information somewhere in the application and query it whenever we desire to return a grapheme. We'll define a convenient struct that we'll store in a

struct Character { unsigned int TextureID; // ID handle of the glyph texture glm::ivec2 Size; // Size of glyph glm::ivec2 Bearing; // Offset from baseline to left/tiptop of glyph unsigned int Advance; // Offset to accelerate to next glyph }; std::map<char, Character> Characters; For this chapter we'll keep things unproblematic by restricting ourselves to the first 128 characters of the ASCII graphic symbol set. For each character, nosotros generate a texture and store its relevant information into a

glPixelStorei(GL_UNPACK_ALIGNMENT, one); // disable byte-alignment brake for (unsigned char c = 0; c < 128; c++) { // load character glyph if (FT_Load_Char(face, c, FT_LOAD_RENDER)) { std::cout << "Mistake::FREETYTPE: Failed to load Glyph" << std::endl; go on; } // generate texture unsigned int texture; glGenTextures (1, &texture); glBindTexture (GL_TEXTURE_2D, texture); glTexImage2D ( GL_TEXTURE_2D, 0, GL_RED, face->glyph->bitmap.width, face up->glyph->bitmap.rows, 0, GL_RED, GL_UNSIGNED_BYTE, face->glyph->bitmap.buffer ); // prepare texture options glTexParameter i(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_S, GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE); glTexParameter i(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_T, GL_CLAMP_TO_EDGE); glTexParameter i(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER, GL_LINEAR); glTexParameter i(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER, GL_LINEAR); // now store graphic symbol for later apply Character character = { texture, glm::ivec2(face up->glyph->bitmap.width, face up->glyph->bitmap.rows), glm::ivec2(face->glyph->bitmap_left, face up->glyph->bitmap_top), face->glyph->accelerate.x }; Characters.insert(std::pair<char, Character>(c, character)); } Within the for loop we list over all the 128 characters of the ASCII set and retrieve their respective character glyphs. For each character: we generate a texture, set its options, and store its metrics. What is interesting to note here is that nosotros apply GL_RED every bit the texture's internalFormat and format arguments. The bitmap generated from the glyph is a grayscale viii-bit epitome where each colour is represented by a single byte. For this reason we'd similar to store each byte of the bitmap buffer every bit the texture's single colour value. Nosotros accomplish this by creating a texture where each byte corresponds to the texture color's cherry-red component (outset byte of its color vector). If we apply a single byte to correspond the colors of a texture nosotros do need to accept care of a restriction of OpenGL:

glPixelStorei(GL_UNPACK_ALIGNMENT, ane); OpenGL requires that textures all take a 4-byte alignment eastward.g. their size is always a multiple of 4 bytes. Normally this won't exist a problem since most textures have a width that is a multiple of 4 and/or use 4 bytes per pixel, but since we now just apply a single byte per pixel, the texture can accept any possible width. Past setting its unpack alignment to 1 we ensure there are no alignment issues (which could cause partition faults).

Be sure to clear FreeType's resources once you lot're finished processing the glyphs:

FT_Done_Face(face); FT_Done_FreeType(ft); Shaders

To render the glyphs we'll be using the following vertex shader:

#version 330 core layout (location = 0) in vec4 vertex; // <vec2 pos, vec2 tex> out vec2 TexCoords; compatible mat4 projection; void chief() { gl_Position = project * vec4(vertex.xy, 0.0, 1.0); TexCoords = vertex.zw; } We combine both the position and texture coordinate data into one

#version 330 core in vec2 TexCoords; out vec4 color; compatible sampler2D text; uniform vec3 textColor; void primary() { vec4 sampled = vec4(1.0, one.0, one.0, texture(text, TexCoords).r); color = vec4(textColor, 1.0) * sampled; } The fragment shader takes 2 uniforms: one is the mono-colored bitmap image of the glyph, and the other is a color uniform for adjusting the text's final colour. We first sample the color value of the bitmap texture. Because the texture's data is stored in just its cherry-red component, we sample the r component of the texture as the sampled alpha value. Past varying the output color's alpha value, the resulting pixel will be transparent for all the glyph's background colors and non-transparent for the actual character pixels. We also multiply the RGB colors by the textColor compatible to vary the text color.

Nosotros do demand to enable blending for this to work though:

glEnable (GL_BLEND); glBlendFunc (GL_SRC_ALPHA, GL_ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA); For the projection matrix nosotros'll be using an orthographic projection matrix. For rendering text we (usually) do not demand perspective, and using an orthographic projection matrix likewise allows the states to specify all vertex coordinates in screen coordinates if we fix it up every bit follows:

glm::mat4 projection = glm::ortho (0.0f, 800.0f, 0.0f, 600.0f); We prepare the projection matrix'due south lesser parameter to 0.0f and its top parameter equal to the window'south height. The event is that nosotros specify coordinates with y values ranging from the bottom part of the screen (0.0f) to the top part of the screen (600.0f). This ways that the point (0.0, 0.0) at present corresponds to the bottom-left corner.

Last up is creating a VBO and VAO for rendering the quads. For at present we reserve enough memory when initiating the VBO so that we tin later update the VBO'south retention when rendering characters:

unsigned int VAO, VBO; glGenVertexArrays (1, &VAO); glGenBuffers (1, &VBO); glBindVertexArray (VAO); glBindBuffer (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, VBO); glBufferData (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeof(float) * half dozen * 4, NULL, GL_DYNAMIC_DRAW); glEnable VertexAttribArray (0); glVertexAttribPointer (0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, four * sizeof(bladder), 0); glBindBuffer (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0); glBindVertexArray (0); The 2D quad requires 6 vertices of 4 floats each, and then we reserve half dozen * 4 floats of memory. Considering nosotros'll exist updating the content of the VBO'southward memory quite often nosotros'll allocate the memory with GL_DYNAMIC_DRAW.

Render line of text

To render a character, nosotros extract the corresponding

Nosotros create a function chosen

void RenderText(Shader &due south, std::string text, float ten, float y, float scale, glm::vec3 colour) { // activate corresponding render state s.Use(); glUniform 3f(glGetUniformLocation (s.Program, "textColor"), colour.ten, colour.y, color.z); glActiveTexture (GL_TEXTURE0); glBindVertexArray (VAO); // iterate through all characters std::string::const_iterator c; for (c = text.begin(); c != text.cease(); c++) { Character ch = Characters[*c]; float xpos = x + ch.Bearing.x * calibration; float ypos = y - (ch.Size.y - ch.Begetting.y) * scale; float w = ch.Size.x * scale; float h = ch.Size.y * calibration; // update VBO for each character bladder vertices[vi][4] = { { xpos, ypos + h, 0.0f, 0.0f }, { xpos, ypos, 0.0f, 1.0f }, { xpos + w, ypos, 1.0f, 1.0f }, { xpos, ypos + h, 0.0f, 0.0f }, { xpos + w, ypos, 1.0f, ane.0f }, { xpos + westward, ypos + h, ane.0f, 0.0f } }; // render glyph texture over quad glBindTexture (GL_TEXTURE_2D, ch.textureID); // update content of VBO retention glBindBuffer (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, VBO); glBufferSubData (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0, sizeof(vertices), vertices); glBindBuffer (GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0); // render quad glDrawArrays (GL_TRIANGLES, 0, 6); // now advance cursors for next glyph (notation that advance is number of 1/64 pixels) x += (ch.Advance >> six) * scale; // bitshift past 6 to get value in pixels (2^half-dozen = 64) } glBindVertexArray (0); glBindTexture (GL_TEXTURE_2D, 0); } Most of the content of the role should be relatively cocky-explanatory: we first summate the origin position of the quad (as xpos and ypos) and the quad's size (equally w and h) and generate a set of vi vertices to form the 2D quad; note that nosotros scale each metric past calibration. We then update the content of the VBO and render the quad.

The following line of lawmaking requires some actress attention though:

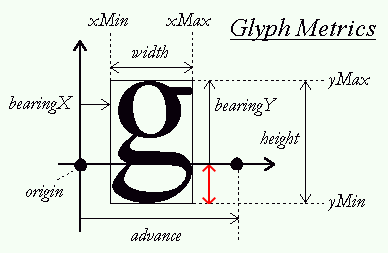

float ypos = y - (ch.Size.y - ch.Begetting.y); Some characters (like 'p' or 'm') are rendered slightly below the baseline, and so the quad should also be positioned slightly beneath

To summate this distance east.one thousand. beginning we need to figure out the distance a glyph extends beneath the baseline; this altitude is indicated past the crimson pointer. As you lot can see from the glyph metrics, we tin calculate the length of this vector by subtracting bearingY from the glyph'due south (bitmap) height. This value is then 0.0 for characters that rest on the baseline (like 'X') and positive for characters that reside slightly below the baseline (like 'k' or 'j').

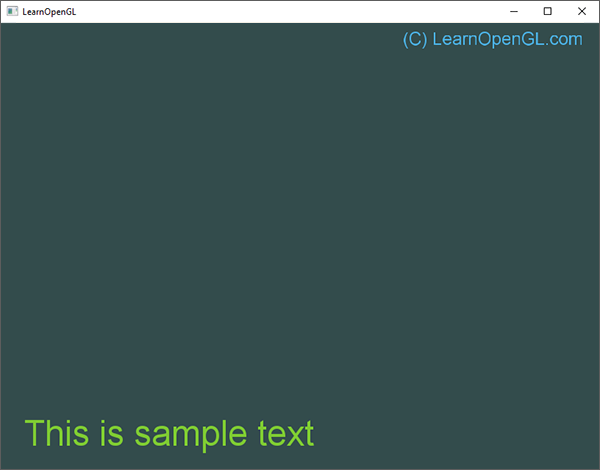

If y'all did everything correct you should now be able to successfully render strings of text with the following statements:

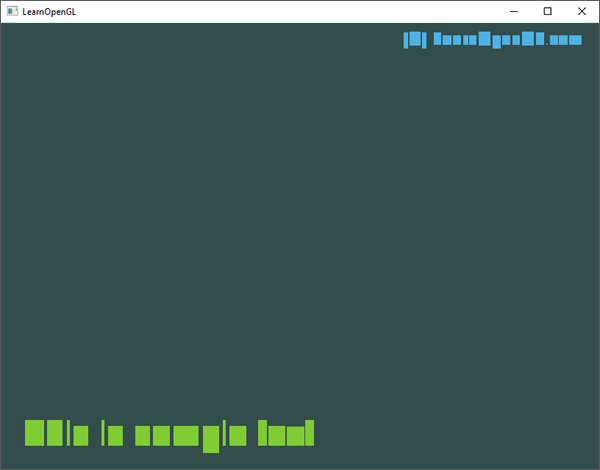

RenderText(shader, "This is sample text", 25.0f, 25.0f, ane.0f, glm::vec3(0.5, 0.8f, 0.2f)); RenderText(shader, "(C) LearnOpenGL.com", 540.0f, 570.0f, 0.5f, glm::vec3(0.3, 0.7f, 0.9f)); This should then look similar to the following image:

Yous can detect the code of this example here.

To requite you a feel for how we calculated the quad's vertices, we can disable blending to see what the bodily rendered quads await like:

Here you can clearly see nigh quads resting on the (imaginary) baseline while the quads that corresponds to glyphs like 'p' or '(' are shifted downwards.

Going further

This chapter demonstrated a text rendering technique with TrueType fonts using the FreeType library. The arroyo is flexible, scalable, and works with many graphic symbol encodings. Even so, this approach is likely going to be overkill for your application as we generate and render textures for each glyph. Performance-wise, bitmap fonts are preferable as we only need one texture for all our glyphs. The all-time approach would be to combine the ii approaches by dynamically generating a bitmap font texture featuring all character glyphs as loaded with FreeType. This saves the renderer from a significant amount of texture switches and, based on how tight each glyph is packed, could relieve quite some performance.

Another upshot with FreeType font bitmaps is that the glyph textures are stored with a stock-still font size, so a pregnant amount of scaling may introduce jagged edges. Furthermore, rotations applied to the glyphs will crusade them to appear blurry. This tin exist mitigated by, instead of storing the actual rasterized pixel colors, storing the distance to the closest glyph outline per pixel. This technique is called

Further reading

- lxx+ Best Gratis Fonts for Designers: summarized list of a large group of fonts to utilise in your project for personal or commercial use.

Source: https://learnopengl.com/In-Practice/Text-Rendering

0 Response to "opengl draw 2d text 3d scene"

Post a Comment